Dopamine offers insights into Parkinson’s and autism

While growing evidence shows that rates of Parkinson’s disease are unusually high in the autistic population, the reason remains unknown. As symptoms of both conditions involve changes to bodily movement and social behaviour, one hypothesis is that they share a biological basis. Benefiting from a cross-disciplinary collaboration – including neuroscience, AI and genetics – the Brain2Bee(opens in new window) project, which was funded by the European Research Council(opens in new window), investigated whether dopamine could offer part of the answer. “While some studies had linked dopamine to autism, dopamine’s role in social behaviour wasn’t well understood, inspiring us to explore a possible broader role in the social and motor functions of autism and Parkinson’s,” says Jennifer Cook, project coordinator from the University of Birmingham(opens in new window), the project host. A key project outcome has been the development of better diagnostic tools. “We’re very excited that our tools can tell autism and Parkinson’s apart based on movement. We had feared the movements might be too similar for the algorithms,” explains Cook. “This offers real hope for faster and more accurate diagnosis of each condition.”

Dopamine affects behaviour, as well as motor functions

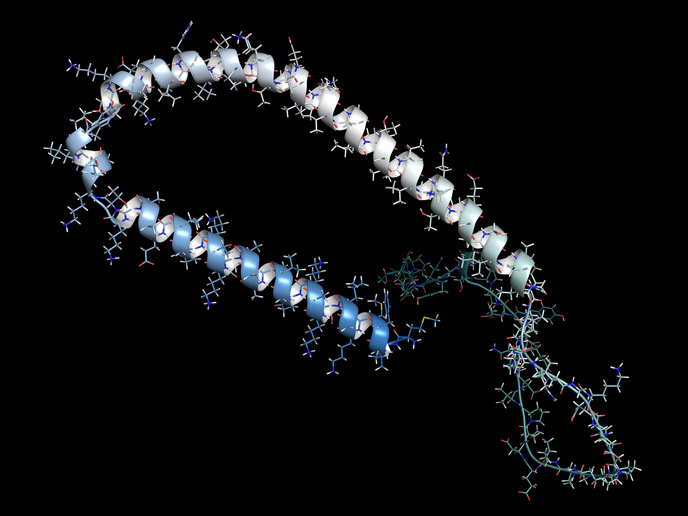

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter made from an amino acid found in foods such as dairy, nuts and seeds. It is known to influence how the brain processes a range of cognitive and bodily functions such as learning and movement. In Parkinson’s, a specific region of the brain loses dopamine-producing cells and so medication is often used to increase levels. Brain2Bee recruited volunteers from amongst the general public for a drug trial. Some participants were given a drug called haloperidol which blocks a dopamine receptor the D2 receptor(opens in new window), temporarily putting the brain in a ‘low dopamine’ state; while others received a placebo. To observe how dopamine influences physical movement and social interaction, participants completed motor and social tasks, with performance compared between days when taking haloperidol and placebo days. Dopamine was found to play a key role in adjusting the speed of movements depending on the situation(opens in new window). Crucially, it was also found to be important for developing social sensitivities, such as understanding the feelings(opens in new window) and intentions of others(opens in new window), and learning from social cues(opens in new window). “Intriguingly, we also found that dopamine affects social and motor functions separately, suggesting different parts of the dopamine system may be involved in each. If confirmed, this could mean that the dopamine’s influences on movement and social behaviours aren’t as connected as thought,” adds Cook. A computer model was developed to investigate whether autism and Parkinson’s share any biological or behavioural features linked to dopamine. Machine learning trained the model’s algorithms to distinguish between autism and Parkinson’s based on data about movement. “We didn’t find a shared genetic cause. Furthermore, our algorithm found key differences in movement patterns, suggesting that despite their similarities, the conditions are quite distinct – paving the way for future tools that reduce misdiagnosis,” notes Cook.

How social behaviour might be conserved across evolution

To explore whether social behaviour is supported by similar genes in other species, Brain2Bee also looked at honeybees, as highly social creatures with brain chemistry comparable to humans (including dopamine). “Analysing genetic data from both species, we found overlap in some genes linked to sociability(opens in new window), suggesting that certain biological pathways for social behaviour might be conserved across evolution,” explains Cook. While outside the scope of Brain2Bee, testing dopamine-enhancing drugs to support social or motor functions, will be an area of future focus.