Multicultural apes, a new view of primate communication

Two universals in human language are grammar and culture: from relatively small sets of sounds, or signs, we can create near infinite meaning by combining them into new structure, and near infinite variation, by continually learning and updating our languages and dialects. Diversity – differences between individuals, groups and cultures, is at the heart of language – whether in our meaning, our grammar or our own communicative development. But the importance of that diversity, and the richness it offers, has not been fully recognised and explored in the study of how apes communicate. Research has often focused on single populations or communities. “It’s as though we had only ever studied language in one small village in Scotland, or Iran or Micronesia,” says Cat Hobaiter(opens in new window), professor of Origins of Mind, at the University of St Andrews(opens in new window) and principal investigator of the GESTURALORIGINS(opens in new window) project. “At the heart of the Linguistic Features of pan-African Ape Communication project is the simple idea that to uncover what is universal or unique about human language, we have to take the same multicultural perspective to our study of other apes’ communication,” she adds.

Comparing how apes construct meaning across time and location

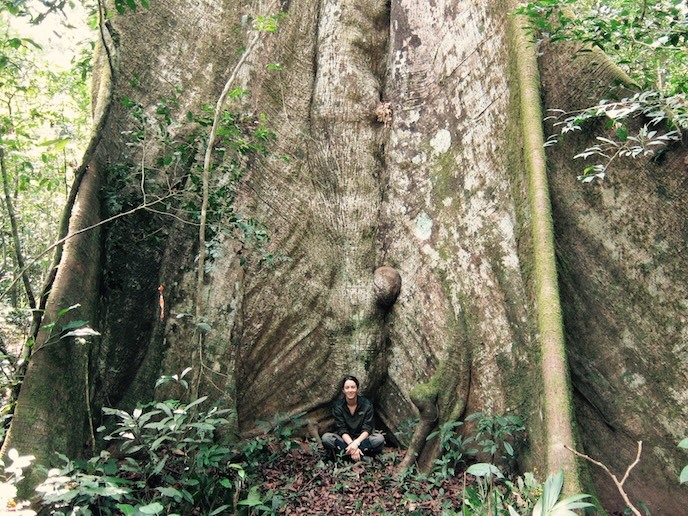

To consider how apes combine signals to construct meaning, and how the speed, size and timing of gestures impacts meaning, the team used several approaches. “We were incredibly lucky to have access to unique long-term archives of ape behavioural video, in some cases covering multiple generations of the same community,” says Hobaiter. This was complemented with fieldwork to study both well-known and new populations of apes across Africa. The team also explored the benefit of online community science: “It turns out people really love watching videos of apes online, and one of our studies had over 15 000 participants!”

The meaning of the same primate gesture changes depending on context

The researchers had already established a method for getting at the core meaning of a gesture by looking at the behaviour that stops the signaller from signalling. “If I’m asking you to pass me the coffee in the morning, I’ll ask and ask, but the one thing that will stop me asking is when you pass me the coffee. In the apes we can also look at the interactions between signallers and recipients to infer what the signaller wanted to achieve.” But one of the most exciting things was to see that apes, like humans, have a lot of flexibility in their meanings. “We can use the same words to mean something very different depending on context and who we are communicating with – for the apes it’s the same. A single gesture can have multiple meanings, but the specific meaning on any one occasion of use depends on who you are communicating with and the wider context you’re in,” Hobaiter explains.

A rich dataset of recorded ape gestures to fuel future research into the origins of language

GESTURALORIGINS, which was funded by the European Research Council(opens in new window), has developed a comprehensive dataset(opens in new window) enabling researchers to apply techniques for studying linguistics to a wide range of recorded gestures(opens in new window), which means that the resource is a real treasure trove, Hobaiter feels. They are only beginning to scratch the surface of what that reveals, and its potential. “The project was incredibly successful, we’ve been able to show – for the first time – that apes show both universals and cultural differences in their communication, just as we see in human language,” she adds. The project has also given her the freedom to move beyond what she thought the project could address, in the study of how language evolves. “We’re starting to think about topics that for most of my career would have only been after-dinner speculation – What were the first words for? How did storytelling shape the ways in which we communicate? Do apes use their communication to shape their sense of individual and social identity?”