Understanding reproductive cooperation in mammals

Some mammals, such as meerkats and mole rats, are unusual in that one breeding female in each social group virtually monopolises reproduction. All other group members assist in raising her offspring and most do not breed themselves.

Benefits and consequences of reproductive cooperation

“Natural selection is usually assumed to favour individuals that maximise their own breeding success,” notes Group-Dynamics-TCB(opens in new window) project coordinator Tim Clutton-Brock from the University of Cambridge(opens in new window) in the United Kingdom. “The breeding systems of these species consequently challenge evolutionary theory, and raise important questions about individual development, group dynamics and population dynamics.” Clutton-Brock wanted to better understand the benefits and consequences of reproductive cooperation through studying two of the most cooperative mammals, Kalahari meerkat and Damaraland mole rats. The Group-Dynamics-TCB project, supported by the European Research Council(opens in new window), enabled him to build on his pre-existing studies in the Kalahari that provided access to large numbers of individuals and groups that were used to the presence of observers.

Measuring individual behaviour and breeding differences

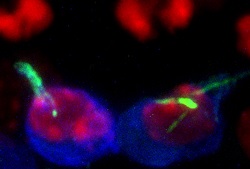

The team was able to measure individual differences in the development, behaviour and breeding success of individuals throughout their lives. They were also able to measure the heritability of differences as well as the effects of variation in their physical and social environments. “The unusual level of habituation in these animals allowed us to drill down to details such as the effects of changes in the rate of weight gain of mothers throughout pregnancy on the subsequent lives of their offspring,” says Clutton-Brock. “In addition, we were able to chart changes in gene function that occur as individuals transition from subordinates to dominants.” The team attached accelerometers to mole rats, enabling them to measure activity levels below ground. These wearable sensors measured movement, from which the team was able to infer a wide range of behaviour and glean valuable biological information such as energy expenditure and activity patterns.

Proliferating genes via the family

A key finding was that, in both species, group members were unusually closely related. This suggests that through helping their mothers or sisters to rear their pups, subordinates increased the proliferation of genes(opens in new window) shared with them. The study also showed that by helping, subordinates increased the size of their group. This could assist in increasing their own survival and eventual breeding success, as well as the number of their own descendants. “We also explored the effects of cooperative breeding on population dynamics,” adds Clutton-Brock. “We showed how increases in group size mitigated the negative consequences of droughts and rising summer temperatures, providing a possible explanation of why cooperative breeding is relatively common in species living in arid, unpredictable areas.” The team was able to show that costly forms of reproductive cooperation, such as feeding other individuals’ offspring, are usually confined to species living in groups of close relatives. The project’s work has led to ongoing collaboration between Clutton-Brock’s team and population geneticists at the Max Planck Institute(opens in new window) for evolutionary anthropology in Leipzig.